Mason Family Saga – Part 2

Before proceeding with more detailed information about family members it is important to pause and note circumstances that affected the Mason family in Canada and later, in the United States at that time.

(much of the following is abridged from Wikiwand.com, Dictionary of Canadian Biography and other websites)

In Canada

The Politics of the Day

John Beverley Robinson, Attorney-General of Upper Canada (bet. 1818-1828), wanted to convert colony reserves to cash so that a permanent sinking fund could be created to prevent the elected Legislative Assembly from forcing the voters’ will upon the Government and Executive Council of Upper Canada through the Assembly’s capacity to cut off tax revenues. A second plan was to use funds from the sale of reserves to repay Upper Canadians for losses to property suffered during the War of 1812. This included losses from American soldiers who burned and pillaged and from British troops who requisitioned homes, seized grain and produce, slaughtered livestock for food and generally showed little concern for the property of those they were defending. The British government soundly squashed these proposals. Thus, Crown Reserve lands were created to provide government revenues.

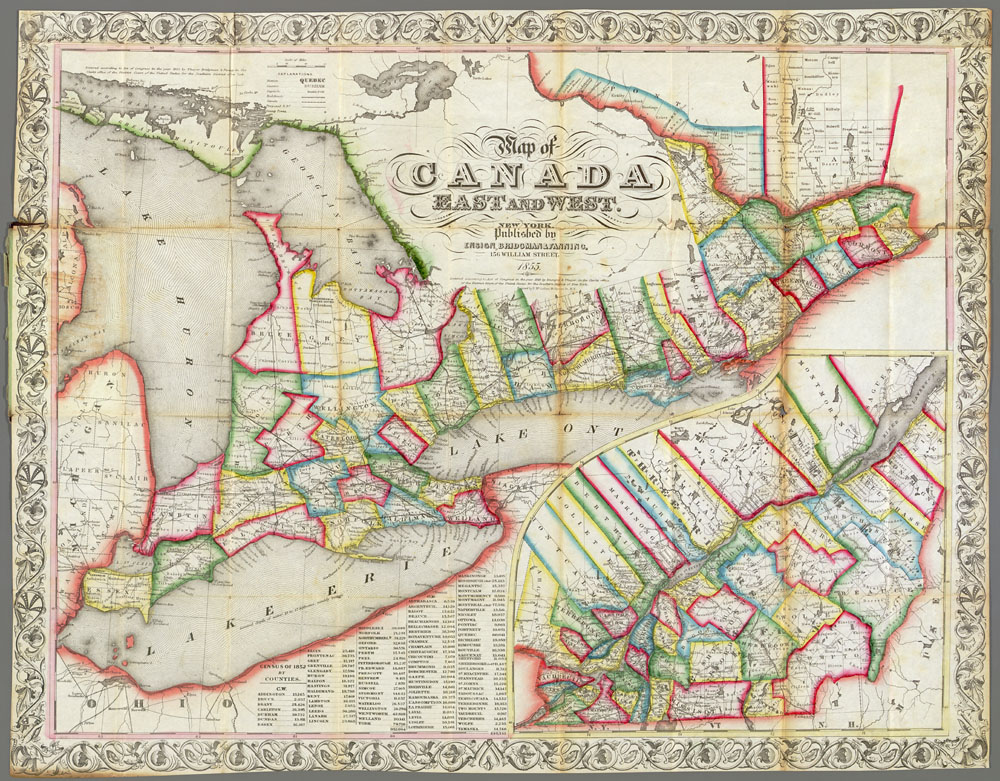

Crown Reserves (one seventh of surveyed lands in all the older surveyed townships and indicated by a pale red blur on early maps) were to be leased rather than sold to provide ongoing government revenue. Very few settlers were willing to make improvements on leased land when there was land that could be purchased outright at a reasonable price. As a result, there was little revenue generated in this way.

Clergy Reserves were created for the support of Protestant clergy by the Constitutional Act of 1791 (one seventh of surveyed lands indicated by a gray smudge on early maps). Clergy and Crown Reserve lands were impediments to the development of roads and community growth in older counties of Upper Canada where the lots were scattered throughout a township. Landowners were required to manage the road allowance adjacent to their property and as no one ‘owned’ the set-aside Clergy and Crown lots, there was no management of the road allowance adjacent to these lots. These ‘undeveloped’ portions of roads made travel difficult. Both Crown and Clergy Reserves were finally abolished in 1854 although some were ‘sold’ prior to this date.

In 1822, a group of war-damage claimants banded together and hired John Galt, a Scottish novelist, to pursue their claims at Whitehall. Initially, Galt had no success in representing his clients to the British authorities. The British government simply refused to consider any kind of cash settlement. Galt gradually evolved the idea of selling the vacant lands of Upper Canada to compensate his clients. He proposed to raise capital of one million pounds and buy all the unsold lands in Upper Canada. Although the Canada Company ultimately fell short of this goal, it was still the largest enterprise of its kind in Canadian history.

In Upper Canada, during the period from 1830-1860, settlers became increasingly frustrated with the land management practices of the prevailing government. The Executive Council of Upper Canada which represented the British parliament – a group of powerful men in York – frequently provided land grants to friends and supporters in return for favours. These large patronage grants of the best lands were given to favourites and were intended to provide the recipient with an elevated position in the area, and to encourage a social order less democratic than what had evolved in communities settled by the United Empire Loyalists and their descendants. The large estates paid no taxes, contributed nothing to the progress of the country, but greatly retarded it in all instances. Marked on early maps with a “D”, some lots were deeded to the ‘favoured persons’, who was often not a resident. Early residents of the military depot of Perth who received grants, sold them to incoming settlers and others who were dissatisfied with their original grant of land. The wealth generated was used to establish businesses and to built the historic stone building for which the town of Perth is known.

The Canada Company

In 1825 John Galt arrived in Canada tasked with the development and sale of undeveloped clergy reserves in the Province of Upper Canada. He was soon to assume responsibility for opening a new parcel of land known as the Huron Tract. By 1826 he formed the Canada Company to manage the sale of over a million acres of land to settlers. This included the existing Clergy and Crown reserves which received little of his attention until much later.

John Galt believed that it was necessary to plan infrastructure for new communities – roads needed to be built, sites for mills and future towns identified and other amenities provided if new communities were to succeed. Often at odds with the government of the day, it is said that John Galt “would have liked to deal with all governments in what he considered their true character – ‘as a committee of the people;’ and when he met with directors of a country who considered that a government should be autocratic, friction ensued”.[1] For many years the Canada Company directed much of its attention to the development of new areas, and neglected its initial task of directing the development of Clergy Reserves. Under the Canada Company undeveloped land was now required to generate revenue and land was no longer available without cost to the settler. To promote settlement of new areas, large tracts of land were granted to land barons tasked with finding appropriate settlers. The scattered lots of older counties continued to be an impediment to efficient community building in the eastern part of the province of Upper Canada.

The Settler Experience in Lanark County

Military and patronage settlers received their patents early in the settlement of Lanark County – some as early as 1820. It appears that military officers would organize members of their regiment to meet settlement requirement on the lots of former regimental members. Some of the 1816 unassisted British settlers had large families and the resources to clear their properties quickly. However, the sponsored settlers of 1820-21 and later would wait many years to receive their patents. Holders of early patents were able to charge significant sums for the sale of their lands.

In the 1820s settlers, placed to rear of the Rideau river in support of British resistance to American invasion, became discouraged and moved to the United States where canals were being built. The land assigned to them was, for the most part rough land, often with surface rock outcropping and much low-lying marsh and swamp. Lanark had pockets of farmland but there were two major hinderances to agricultural development – the scattered nature of arable land and the lack of transportation routes to markets. Few could repay government loans and fees required to obtain their land patents.

Once on American soil, canal workers often connected with people who aborted their plan to settle in Canada when enticed to cross the St. Lawrence River and take up offers of land In New York State. Through letters to friends and family who continued to the planned destination in Lanark County they transmitted information about American ways and thoughts. On the completion of the canals, some Lanark workers settled in the United States. Those who returned brought their experiences back to Canada.

In 1834, Colonel Marshall was directed to survey the circumstances of the sponsored settlers who settled in 1820-21 in the townships of Lanark, Dalhousie, North Sherbrooke and Ramsay. As a result of his report, repayment of loans was forgiven, and land patents granted to those still present on their lots.

Those who settled in the townships of South Sherbrooke, Bathurst, Drummond and Beckwith did not fair as well. Many of the early deeded lots in these townships were owned by people who lived elsewhere or who sought financial benefit from their patronage grants. Clergy and Crown Reserve land were requested by settlers during the 1830s and 1840s but were not made available to settlers until much later. Few of these lots had attracted permanent residents. Those who chose to remain, often to be close to family members, spent many years seeking the patent to these lots. Many patents were delayed even when a purchaser had appropriate documentation of purchase and sale from original grantees.

Into Simcoe County and Huron Tract Lands

As development proceeded along the shores of lake Ontario, settlement pushed northward from the lake. Simcoe County, west of Lake Simcoe, especially the township of Innisfil, attracted many of the now-grown children of early Lanark County settlers who sought land of their own. Simcoe County offered larger areas of arable land, roads south to York and markets, and communities with mills and other amenities.

In the 1830s Malcolm Cameron, a merchant and publisher in Perth for a short time, soon transferred his interest in the Perth area to Port Sarnia in the Huron Tract where good farmland was available for development. He encouraged early military and former weavers who had settled in Lanark County to join him. Cameron was influenced by the Scottish ‘Radicals’ who had settled around Lanark Village and agreed to run as a moderate Reformer for Lanark in 1836. In 1837, the year of the Rebellion in favour of responsible government, he generally opposed Sir Francis Bond Head and the oligarchy then in power. The Canadian reformers took their inspiration from the republicanism of the American Revolution where the Patriots held an intense fear of political corruption and the threat it posed to liberty. By 1835, the Huron Tract had been surveyed and was abolished in favour of the counties of Huron, Middlesex and Kent counties. By the 1850s, the sons of settlers were finding their way to the Bruce Peninsula as Bruce and Grey Counties opened for settlement.

Settlement in the United States

The first wave of Lanark County settlers to immigrate to the United States occurred during the 1820s. Some of these people returned to Lanark County after the canals were completed but many settled in New York state. Over the following years some of these individuals and others from the Lanark community migrated further to the west as Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, and North and South Dakota opened to settlers.

Michigan

In 1763, by the Treaty of Paris, Great Britain acquired jurisdiction over Canada and the French territory east of the Mississippi River except for New Orleans. Under British rule Michigan remained a part of Canada. The area that would become Michigan was awarded to the United States in 1783. In 1805 Michigan Territory was separated from Indiana, and Detroit was made its capital. In 1818 steamship navigation linked Detroit and Buffalo (N.Y.), inaugurating a new era in lake transportation. Road links were established between Detroit, Chicago Il. Saginaw MI and Port Huron MI. Completion of the Erie Canal in 1825 made Michigan even more appealing for settlers seeking new homes in the Great Lakes area; the canal provided easy access to the region from the east by water, and further, it opened up the markets of the east coast to Michigan products such as wheat. Statehood was declared in 1836. New settlement occurred during the period of ‘Michigan Fever’ 1840s and 1850s. Thousands of prospective agricultural settlers—including many who came from Canada, New York and the New England states via the Erie Canal and Lake Erie, as well as many who were foreign-born—established new homes in the state. Iron ore and copper mining in the Upper Peninsula and lumbering of the vast pine forests was the mainstay of the state’s economy during the late 1800s.[2]

Wisconsin

The area to become Wisconsin remained under French control until 1763, when it was acquired by the British. It was subsequently ceded to the United States by the Peace of Paris treaties in 1783 but continued to be controlled by the British who continued the local fur trade and maintain military alliances with Wisconsin First Nation peoples in an effort to stall American expansion westward. The United States did not firmly exercise control over Wisconsin until the War of 1812 when Britain retreated and the United States built forts to protect the Michigan territory (incl. Wisconsin, Minnesota and Iowa & part of North and South Dakota).[3] Under American control, the economy of the territory shifted from fur trading to lead mining. By 1829 more than 4,000 lead miners, many from Cornwall England, worked in southwestern Wisconsin, in and around Mineral Point.[4] Lead mining was the first large industry.

Land Offices open in 1834 at Green Bay and Mineral Point. The Wisconsin Territory (consisting of present-day Wisconsin, Iowa, Minnesota, and parts of North and South Dakota) was created in 1836. Two years later the territory became smaller when land west of the Mississippi became part of Iowa Territory.

Between the 1840s and 1860s, settlers from New England, New York and Germany arrived in Wisconsin. Some of them brought radical political ideas to the state. In the 1850s, stop-overs on the underground railroad were set up in the state and abolitionist groups were formed. One such group was the Republican Party. On March 20, 1854, the first county meeting of the Republican Party of the United States, consisting of about thirty people, was held in the Little White Schoolhouse in Ripon, Wisconsin. Ripon claims to be the birthplace of the Republican Party, as does Jackson, Michigan, where the first statewide convention was held.

A railroad frenzy swept Wisconsin shortly after it achieved statehood in 1848. The first railroad line in the state was opened between Milwaukee and Waukesha in 1851 by the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad. The railroad pushed on, reaching Milton, Wisconsin in 1852, Stoughton, Wisconsin in 1853, and the capital city of Madison in 1854. The company reached its goal of completing a rail line across the state from Lake Michigan to the Mississippi River when the line to Prairie du Chien was completed in 1857. By 1850 the population of Wisconsin had increased from about 30,000 to more than 300,000, and most of the agriculturally suitable areas had been occupied by 1880.

Agriculture was a major component of the Wisconsin economy during the 19th century. Wheat was a primary crop on early Wisconsin farms. In fact, during the mid 19th century, Wisconsin produced about one sixth of the wheat grown in the United States. However, wheat rapidly depleted nutrients in the soil, especially nitrogen, and was vulnerable to insects, bad weather, and wheat leaf rust. In the 1860s, chinch bugs arrived in Wisconsin and damaged wheat across the state. As the soil lost its quality and prices dropped, the practice of wheat farming moved west into Iowa and Minnesota. Some Wisconsin farmers responded by experimenting with crop rotation and other methods to restore the soil’s fertility, but a larger number turned to alternatives to wheat.

Meanwhile, the lumber industry dominated in the heavily forested northern sections of Wisconsin, and sawmills sprang up in cities like La Crosse, Eau Claire, and Wausau. By the close of the 19th century, intensive agriculture had devastated soil fertility, and lumbering had deforested most of the state. These conditions forced both wheat agriculture and the lumber industry into a precipitous decline.[5]

The first brewery in Wisconsin was opened in 1835 in Mineral Point by brewer John Phillips. A year later, he opened a second brewery in Elk Grove. In 1840, the first brewery in Milwaukee was opened by Richard G. Owens, William Pawlett, and John Davis, all Welsh immigrants. By 1860, nearly 200 breweries operated in Wisconsin, more than 40 of them in Milwaukee. The huge growth in the brewing industry can be accredited, in part, to the influx of German immigrants to Wisconsin in the 1840s and 1850s.

Minnesota[6]

All the land east of the Mississippi River was granted to the United States by the Second Treaty of Paris at the end of the American Revolution in 1783. Throughout the first half of the 19th century, the northeastern portion of the state was a part of the Northwest Territory, then the Illinois Territory, then the Michigan Territory, and finally the Wisconsin Territory. Most of the state was purchased in 1803 from France as part of the Louisiana Purchase. Parts of northern Minnesota were considered part of Rupert’s Land. The exact definition of the boundary between Minnesota and British North America was not addressed until the Anglo-American Convention of 1818, which set the U.S.–Canada border at the 49th parallel west of the Lake of the Woods (except for a small chunk of land now dubbed the Northwest Angle). Border disputes east of the Lake of the Woods continued until the Webster-Ashburton Treaty of 1842. The western and southern areas of the state, although theoretically part of the Wisconsin Territory from its creation in 1836, were not formally organized until 1838, when they became part of the Iowa Territory.

The Minnesota Territory was established from the lands remaining from Iowa Territory and Wisconsin Territory on March 3, 1849. The Minnesota Territory extended far into what is now North Dakota and South Dakota, to the Missouri River. Minnesota became the 32nd U.S. state in 1858.

The Homestead Act in 1862 facilitated land claims by settlers, who regarded the land as being cheap and fertile. The American Civil War (1861-1865) and the Dakota War of 1862 (an armed conflict between the United States and several bands of Dakota also known as the eastern Sioux) made it a turbulent time for settlement. The land was divided into townships and plots for settlement. Logging and agriculture on these plots eliminated surrounding forests and prairies, which interrupted the Dakota’s annual cycle of farming, hunting, fishing and gathering wild rice. Hunting by settlers dramatically reduced wild game, such as bison, elk, whitetail deer and bear. Not only did this decrease the meat available for the Dakota in southern and western Minnesota, but it directly reduced their ability to sell furs to traders for additional supplies. Add to this, fraud committed by agents a general disregard for signed treaties, and delays in the delivery of money and food, the Dakota people were faced with starvation. The arrival of settlers led to a fight for survival. The conflict led to the expulsion of the unassimilated Dakota from Minnesota and Iowa. The Minnesota River valley and surrounding upland prairie areas were abandoned by most settlers during the war. Many of the families who fled their farms and homes as refugees never returned.

Following the American Civil War, however, the area was resettled. By the mid-1870s, it was again being used and developed by European Americans for agriculture. After the upheaval of the American Civil War and the Dakota War the state’s economy started to develop when natural resources were tapped for logging and farming. Railroads attracted immigrants, established the farm economy, and brought goods to market. The power provided by St. Anthony Falls spurred the growth of Minneapolis, and the innovative milling methods gave it the title of the “milling capital of the world”.

The railroad industry, led by the Northern Pacific Railway and Saint Paul and Pacific Railroad, advertised the many opportunities in the state and worked to get immigrants to settle in Minnesota. James J. Hill was instrumental in reorganizing the Saint Paul and Pacific Railroad and extending lines from the Minneapolis-Saint Paul area into the Red River Valley and to Winnipeg. Hill was also responsible for building a new passenger depot in Minneapolis, served by the landmark Stone Arch Bridge which was completed in 1883. During the 1880s, Hill continued building tracks through North Dakota and Montana. In 1890, the railroad, now known as the Great Northern Railway, started building tracks through the mountains west to Seattle.

Since there was little or no competition between railroads serving Minnesota farm communities, railroads could charge as much as the traffic would bear. By 1871, the situation was so heated that both the Republican and Democratic candidates in state elections promised to regulate railroad rates. The state established an office of railroad commissioner and imposed maximum charges for shipping.

Saint Anthony Falls, the only waterfall of its height on the Mississippi, played an important part in the development of Minneapolis. The power of the waterfall first fueled sawmills, but later it was tapped to serve flour mills. In 1870, only a small number of flour mills were in the Minneapolis area, but by 1900 Minnesota mills were grinding 14.1% of the nation’s grain. Advances in transportation, milling technology, and waterpower combined to give Minneapolis a dominance in the milling industry. Spring wheat could be sown in the spring and harvested in late summer, but it posed special problems for milling. To get around these problems, Minneapolis millers made use of new technology. They invented the middlings purifier, a device that used jets of air to remove the husks from the flour early in the milling process. They also started using roller mills, as opposed to grindstones. A series of rollers gradually broke down the kernels and integrated the gluten with the starch. These improvements led to the production of “patent” flour, which commanded almost double the price of “bakers” or “clear” flour, which it replaced.

North Dakota

North Dakota was admitted to the Union on November 2, 1889, along with its neighboring state, South Dakota. They were the 39th and 40th states admitted to the union.

Few white settlers travelled to the North Dakota region before the 1870s because railroads had not yet entered the area. During the early 1870s, the Northern Pacific Railroad began to push across the Dakota Territory and brought large-scale farming with it. Eastern corporations and some families established huge wheat farms covering large areas of land in the Red River Valley. The farms made such enormous profits they were called bonanza farms. White settlers, attracted by the success of the bonanza farms, flocked to North Dakota, rapidly increasing the territory’s population. In 1870, North Dakota had 2,405 people. By 1890, the population had grown to 190,983.

Members of the Mason Family participated in many of these migrations.

Link: Part 1 http://diane-duncan.com/2020/10/19/mason-family-saga-part-1/

[1] In the Days of the Canada Company. Robina and Kathleen MacFarlane Liars. William Briggs publisher, Toronto, 1896, pg26.

[2] https://www.britannica.com/place/Michigan/History

[3] https://www.wikiwand.com/en/History_of_Wisconsin#/The_territorial_period

[4] https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Wisconsin

[5] https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Wisconsin

[6] Based on excerpts from https://www.wikiwand.com/en/History_of_Wisconsin