The World I Entered – Part 4 – Immigration

March 1946

Movement of troops back to Canada was well underway. Along with the soldiers, wives and families were given assistance in traveling to Canada.

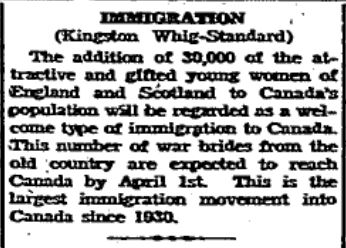

War Brides Arrive

This term gained popular currency during WWII to describe women who married Canadian servicemen overseas and then immigrated to Canada after the war to join their husbands. It is now also used to describe women who had similar experiences after WWI. By the end of 1946, there had been 47 783 marriages between Canadian men and European women, which produced 21 950 children. The vast majority (44 886) were from Great Britain, with much smaller numbers coming from Holland, Belgium, France and elsewhere. Some 80% married soldiers, whereas 18% married men in the RCAF and the remainder married men in the navy. Although all of the servicemen’s wives were eligible to come to Canada, an estimated 4500 war brides declined to make the trip. By 31 March 1948, the Canadian government had transported 43 454 wives and 20 997 children to Canada.

I still need to identify war brides in the family. I’m hoping family members will help with this.

Immigration Policy On People’s Minds

A ‘yes and no’ response to proposed post-war immigration policy.

1945-1947 In the immediate post-war period, immigration controls remained tight, while pressure mounted for a more open immigration policy and a humanitarian response to the displaced persons in Europe.

Local Concerns – Perth Courier Editorials 7 Mar 1946

The following table summarizes the progression on thought in the post war years.

from the Canadian Encyclopedia

| 1946 | The Canadian National Committee for Refugees advised a parliamentary committee that Canadian law should be changed to exempt refugees from ordinary restrictions on immigration and subject them only “to whatever special restrictions on immigration considered by Parliament to be necessary and justifiable in face of the moral claim of the refugees to the right of sanctuary.” |

| 1948 | The first of a total of 10 boats carrying 1,593 Baltic refugees (mostly Estonian) arrived on the east coast of Canada. They sailed from Sweden, where they were living under threat of forced repatriation to the Soviet Union. They had been trying to resettle to Canada but had been frustrated by the long delays and barriers in Canadian immigration processing. They were detained on arrival and processed through an ad hoc arrangement. 12 were deported but all the others were accepted. |

| 1946-1962 | Canada admitted nearly a quarter of a million refugees. They came as sponsored relatives, under contract labour schemes, or sponsored by government or church groups. Selection criteria were guided by considerations of economic self-interest, racial prejudice and political bias. According to John Holmes, an External Affairs officer, Canada selected refugees “like good beef cattle”. |

People Who Passed Through My Life

During my early childhood there were a series of men who worked on our farm. Some stayed a short time, others longer. Horst Zollner returned later with his family to visit us. Another of the men who worked with Dad also returned to visit. For a while I corresponded with the daughter of one, Segrid Fedoro, I think it was. I believe they lived in the Toronto area.

Memories of these men has led me to collect some information about immigration laws in the post war era. I have liberally used the various links indicated to gather this material for future reference (sharing my research notes) and would encourage the reader to visit the source sites.

1953, Horst Zollner, One of several “Displaced Persons” who worked on our farm after WW II.

Background on Canadian Immigration Policy

from Brief history of Canada’s responses to refugees

Immigration Policy

In 1870, just after Confederation, Canada’s total population was 3.6 million. In addition to Indigenous peoples (about 102,000 in 1870) the two largest groups were French (one million) and British (2.1 million). With such a small population, and vast areas of unsettled territory, immigration was seen in the decades after Confederation as a crucial way of expanding the country and its economy.

Over the next century and a half, Canada’s population grew almost ten-fold, to more than 35 million in 2016, much of it through immigration. In recent decades, as Canada’s birth rate has declined, immigration has accounted for the bulk of population growth. Of the six million added to Canada’s population between 1996 and 2016, two-thirds – four million people – were immigrants.

19th Century: Open Doors

In the 19th century, the movement of individuals and groups to Canada was largely unrestricted, except for the ill, the disabled and the poor — groups targeted by the first Immigration Act, passed in 1869.

The other exception, beginning in the 1880s, were Chinese migrants. In 1885, under pressure from British Columbia, a federal law was passed restricting Chinese immigration through the imposition of a head tax (which lasted until 1923) – the first of a series of such measures directed at the Chinese that continued until the late 1940s.

Otherwise, Canada’s immigration policy was concerned mainly with the responsibilities of transportation companies to the people they were carrying to Canada’s shores, and the exclusion of criminals, the sick, and the poor or destitute.

Early 20th Century: Racial and National Restrictions

After massive waves of mostly European immigration to Canada between 1903 and 1913, and a series of political upheavals and economic problems that followed the First World War, a much more restrictive immigration policy was implemented. Under a revised Immigration Act in 1919, the government excluded certain groups from entering the country, including Communists, Mennonites, Doukhobors and other groups with particular religious practices, and also nationalities whose countries had fought against Canada during the First World War, such as Austrians, Hungarians and Turks. (In 1911 the government had considered, but not followed through, on banning Black immigrants.) These restrictive policies and practices continued until the middle of the 20th century.

Post-War Period: First Signs of Change

Canada’s restrictive immigration policies began to slowly and gradually ease after the Second World War, partly thanks to booming economic growth (and demand for labour) and partly due to changing social attitudes.

In 1946 the formal ban on Chinese immigration was ended. In 1952, a new Immigration Act continued Canada’s discriminatory policies against non-European and non-American immigrants.

Post WWII Policy

Source: Family Search

There was no immediate change in immigration policy after the end of WWII for several reasons. There was a real fear of a post war recession as had occurred after WWI; there was a lack of suitable ships to bring people from Europe to Canada; and there was a lack of immigration officers to process new arrivals. However, the tide of opinion was shifting and a growing number of Canadians were now in favour of a lowering of the immigration barriers. As well, there were now over one million displaced persons and refugees in European shelters maintained and supported by United Nations agencies. Many of those who had been uprooted or displaced by the war had no interest in returning home to countries now controlled by communist regimes.

- “Refugees by strict definition, were all those people who had fled totalitarian regimes before the outbreak of the war and those who, starting in the second half of 1945, had left East European countries that had come under Communist control. No matter what their designation though, all these individuals were virtually refugees without a country, home, material possessions, or future.” (Knowles 1992, 120)

A Bill passed in May of 1946 allowed residents of Canada to sponsor first-degree relatives in Europe plus orphaned nieces and nephews under the age of 16. The one caveat was that the sponsors had to be able to care for those they sponsored. A major problem for officials was that many of these displaced immigrants had no passports so provisions were made to accept other forms of identification such as travel documents.

An order-in-council passed in 1946 allowed for the admission of 3000 Polish soldiers. These soldiers had been placed under British army command after Poland’s surrender in 1940. None of them wanted to return to a homeland now under communist rule.

By 1947 it was evident that Canada had made the shift from wartime to peacetime economy, that economic expansion lay ahead and that more workers would be needed. Changes to the immigration act in 1947 allowed for the entry of numbers of immigrants to meet the country’s labour requirements but stipulated that this be accomplished without altering the fundamental character of the Canadian population. Thus a new term arose in immigration lingo: “absorptive capacity”. Attributed to Prime Minister Mackenzie King, this concept allowed the government to make decisions from year to year (or event to event) regarding which groups and what numbers would be allowed to immigrate to Canada. British subjects as well as people from the U.S. and France could come freely but all other cases would be determined on a discretionary basis. Also recognized was that the government had two responsibilities pertaining to immigration:

- to provide the workers needed by the country

- to protect the standard of living of Canadians

Between January 1946 and December 31, 1953 over 750,000 immigrants came to Canada. In deference to the United Nations charter, the Chinese Immigration Act was repealed and Chinese residents of Canada were now allowed to apply for naturalization. Canada also now accepted that she had a moral obligation to assist in easing the refugee problem.

An order-in-council in June 1947 authorized the entry of 5,000 non-sponsored displaced persons. By October 1949 the numbers had risen to 45,000. The government established five mobile immigration teams composed of immigration, security, medical and labour officials. These teams were sent to Germany and Austria in the summer of 1947 to select refugees from the camps deemed acceptable candidates to emigrate to Canada. It’s interesting to note that between 1947 and 1962 about 250,000 displaced persons were admitted and of the 165,000 refugees who came to Canada between 1947 and 1953, the largest group was from Poland (23%).

Another group of displaced persons ranked high on the list of Canadian immigrant teams—people from the Baltic countries. They were in United Nations run camps in Austria and Germany after their home countries, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania were caught in the middle of the Soviet and German battles. They were occupied by the Soviets in 1940, then invaded by Germany and in 1944 had to deal with the advances by the Russian army.

Between 1947 and 1949 about 16,000 Dutch farmers and their families came to Canada. Many of these farmers had lost their land to flooding when the retreating German forces destroyed the dykes. They settled in Ontario, Quebec, Manitoba, Alberta and British Columbia.

In 1950 a new order-in-council replaced all former ones pertaining to immigration. While the preference for British, Irish, French and American immigrants was maintained, the admissible classes of European immigrants were widened “to include any healthy applicant of good character who had skills needed in Canada and who could easily integrate into Canadian society” (Knowles 2000, 72). In that same year regulations were loosened on the entry of Asians, and German immigrants were removed from the enemy-alien list.

In 1950 the government also established the Department of Citizenship and Immigration thereby giving the responsibility for immigration to a new department with two separate branches—one for citizenship and one for immigration. This development ensured that immigration received the visibility and attention required during Canada’s post-war period of growth.

A new Immigration Act in 1952 simplified the administration and defined the powers of the minister and the department’s officials. The Act gave cabinet a large degree of discretionary power to:

- “… limit the admission of persons by reason of such factors as nationality, ethnic group, occupation, lifestyle, unsuitability with regard to Canada’s climate, and perceived inability to become readily assimilated into Canadian society.” (Knowles 2000, 73)

This new act also allowed the minister to act quickly in times of urgency, by bestowing on the office the authority to make on the spot decisions and to cut through administrative red tape.

Canada discouraged the arrival of non-preferred ethnic groups, particularly those coming form oriental and Mediterranean countries. … Not only Chinese or Indians, but the Canadian Government recognized the French nationals to be “non-preferred” until 1948, when PC 4186 allowed any citizen from France to immigrate to Canada as long as they had sufficient financial support until they found employment.

Germans were one of Canada’s most favorite immigrants, regardless of them being enemy alien after WWII. …By 1952, to sustain and keep such racial preferences, the Canadian government essentially the erased the title “enemy aliens” against Italy and Germany.

The Citizenship Act of 1947 was passed by the Canadian government, in order to create Canadian citizenship independent of the British status. To obtain Canadian citizenship, the potential citizen must acquire admission to Canada legally, have 5 years residency in this nation before application, have evidence of a good person (characteristics), sufficient knowledge of either English or French (or 20 years of residence), sufficient knowledge of responsibilities and privileges of Canadian citizenship, and to state an oath-like statement to reside permanently in Canada.

Displaced Persons were permitted into Canada under the sponsored labour scheme, which mandated them to sign a contract agreeing that they would work in fields of either farming, mining, domestic service, railway work, or other forms of manual labour for at least 2 years. Female Displaced Persons were only permitted to come to Canada as domestic contract workers between the years 1947 and 1952.